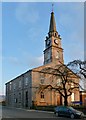

Dumbarton Riverside Parish Church

For a wider view, with more context, see

Image

For a selection of other contributors' pictures of the building, see

Image /

Image /

Image /

Image /

Image The present photograph was taken just a few minutes before sunset; the moon can be seen to the right of the steeple.

A good source of information on this church is the booklet "Dumbarton Parish Church in History", originally by Edward McGhie, and revised and enlarged by David Wilson; it contains a great deal more information than the present item.

The authors note that there is likely to have been a parish church at the time when Dumbarton was erected a Royal Burgh by Alexander II in 1222; they suggest that it was probably similar in size and form to the ancient parish church of Cardross, whose ruins can still be seen in Levengrove Park: http://www.geograph.org.uk/snippet/5737

Any such small building was superseded by the medieval church, which stood in the same place as the present church. It is depicted in a sketch of 1747 by Paul Sandby; from its appearance in that sketch, which is a view of the parish church from the south-east, it is thought to have displayed architectural features typical of the fourteenth or fifteenth century; it has been noted that the building, as depicted in the sketch, with its squat steeple, is similar to the still-extant St Monan's Church (

Image) in Fife; see, for example,

Image

Dumbarton Parish Church is known to have been enlarged in the seventeenth century to give a T-shaped plan. Sandby's sketch also shows, beside the north-eastern corner of the church, the unfinished Buchanan Hospital, on which more will be said below. The sketch also shows various gravestones in the kirkyard: some upright stones, and quite a few table-top stones.

As far as documentary evidence goes, the first mention of the Parish Church is in a charter of 1320 by King Robert the Bruce; in that charter, Robert transfers his right of patronage of the church to Kilwinning Abbey. The first mention of the church in Dumbarton's burgh records dates from 1372.

The medieval church is described (in its post-Reformation state, with various altars removed) by Dumbarton's early historian John Glen, in his 1847 "History of the Town and Castle of Dumbarton". For a time, until 1761, the town's Grammar School appears to have been based in a vaulted chamber under the steeple.

The building of a new church was proposed in 1810. The architect was John Brash, whose first design was rejected as too large and elaborate. The authors of "Dumbarton Parish Church in History" note the similarity of the final design of the church, as shown in the present photograph, to that of

Image, which was also designed by Brash. The present-day Dumbarton Parish Church was opened by the minister James Oliphant on the 28th of July 1811 (Oliphant's own gravestone is nearby, in an enclosure adjoining the eastern end of the kirkyard:

Image).

At the time of writing, the church is known as Dumbarton Riverside Parish Church.

According to the architectural description given in "The Buildings of Scotland: Stirling and Central Scotland" (John Gifford and Frank Arneil Walker; 2002), the gate-piers (

Image) date from 1813, and the illuminated clock dials, by JB Joyce & Co of Whitchurch, Shropshire, were mounted in 1901 – see

Image (The book actually says "J.T.Joyce", a minor slip that I have corrected here.)

- - • - -

The kirkyard associated with the church used to be more extensive, but it has been diminished in several stages, most notably in the 1970s, when much of what remained of the kirkyard was cleared away to make space for the present-day church halls. Before that happened, the memorials with legible inscriptions were photographically recorded.

Only a small number of the original memorials now remain, although

Image and the Barnhill Vault (now containing

Image and

Image) survive to this day; they were legally considered as being separate from the kirkyard proper. The history of the kirkyard and of its reduction in size, and the various controversies that arose in connection with this, have been discussed at length in a separate article – http://www.geograph.org.uk/article/Dumbarton-Cemetery#the-parish-churchyard – and that information need not be repeated here.

For pictures of some of the remaining memorials, click on the end-note title, below.

- - • - -

As for the Buchanan Hospital that was mentioned above, no traces remain above ground, although it is possible that some buried traces survive under or near the present-day church halls. The building extended eastwards from the north-eastern corner of the parish church, and it is depicted, in an unfinished state, in Paul Sandby's sketch of 1747.

There are references in Dumbarton's Burgh Records from as early as 1630 regarding preparations for building the hospital, which was to be endowed by the Laird of Buchanan (Sir John Buchanan). For example, an entry from 25 June of that year describes difficulties in getting materials unloaded at the shore: "the staines that ar to be caryit be boit to the kirk yaird for the bigging of the hospital can not weill win to for the heiht of the sand". An entry of 13 May 1634 records that the work was to be discontinued until certain difficulties could be resolved with the Laird of Buchanan.

There appear to have been some financial problems; an entry for 14 May 1635 speaks of the Provost being urged to "tak the best cours he can for getting that thousand pund awand to the hospitall be umqu[hill] Sir George Elphinstoune". An entry for 18 January 1636 records that obstacles to beginning the work had been removed: "the Laird of Buchanane writes that staine, lyme, sand, and uthir materialls for the hospitall ar reddie, q[uhe]rby the maissons may entir the first of Marche", although the same entry notes that money was still owed, with "Law to be put into exec[utio]n againe Drumakill for that thousand punds, and againe him and Fulwood his cau[tio]n[e]r for aucht hunder merks awand to the hospitall".

The hospital was endowed with £1021, and entrusted to the care of the Kirk Session and the Town Council, but it is unclear whether it was ever completed or occupied. In any case, the houses in Beggar Row (now long gone) on Castle Street were built using its debris [Donald Macleod in "Dumbarton Ancient and Modern"].

In the 1650s, the Burgh's Common Good Accounts note several payments of interest on a sum of 800 pounds owed to the hospital and kirk session; more specifically, payment was to go to the "poores box". The Buchanan Mortification Fund, as it came to be known, continued to be used for poor relief. "In 1655, the Town Council had decided to use part of the money, given by Sir John Buchanan for a hospital, for the maintenance of another minister, and the interest of the rest for poor relief" ["Dumbarton Common Good Accounts, 1614-1660", note 6 on page 221].

Donald MacLeod devotes pages 42 and 43 of his 1884 work "Dumbarton, Vale of Leven, and Loch Lomond" to a discussion of the "Alms-House and Hospital": "This building, which stood immediately to the east of the Parish Church, is supposed to have been erected in either the 14th or 15th century" (he appears to be speaking here of the Alms-house as something distinct from the hospital, since he goes on to say that "it was the Laird of Buchanan who erected the hospital" in 1636). MacLeod adds, regarding the Alms-house, that names of donors, and the amounts of their donations, were displayed on painted boards hung along the walls of the Parish Church, Buchanan of Auchmar being the principal contributor. He states that in 1759, stones from the building (by then a ruin) were used to build a bridge over the "Gallow Mollen/Mollan" (MacLeod appears to view this as another name for the now largely culverted Knowle Burn, also sometimes called the Mill Burn; it formed the eastern boundary of the medieval burgh of Dumbarton). He then discusses the Buchanan Hospital, and the circumstances that led to its funds becoming reduced; he says that the original documents relating to this fund are lost, having last been read, as far as is known, on the 9th of January 1786.