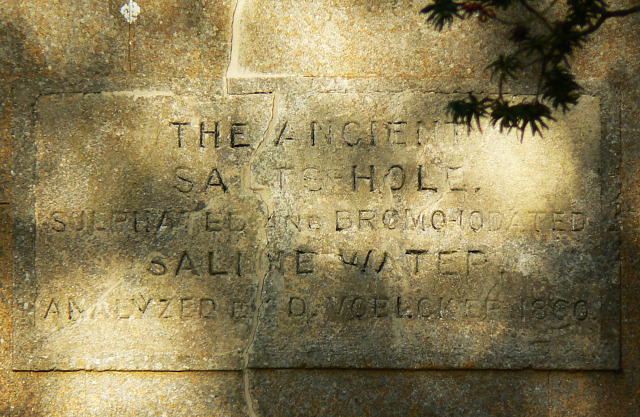

Plaque, Salts Hole, Purton Stoke

Introduction

The photograph on this page of Plaque, Salts Hole, Purton Stoke by Brian Robert Marshall as part of the Geograph project.

The Geograph project started in 2005 with the aim of publishing, organising and preserving representative images for every square kilometre of Great Britain, Ireland and the Isle of Man.

There are currently over 7.5m images from over 14,400 individuals and you can help contribute to the project by visiting https://www.geograph.org.uk

Image: © Brian Robert Marshall Taken: 27 Dec 2009

The plaque reads, "The Ancient Salts Hole. Sulphated and Bromo-iodated saline water. Analyzed by D. Voelcker 1860." From people.bath.ac.uk we learn that: "Salt’s Hole, or Purton Spa There is one remarkable well which made the (surprisingly) unusual transition from healing well to medicinal spa: Salt’s Hole at Purton Stoke. We are well informed of its healing powers because its healing properties were scrupulously documented in publicity materials during its heyday as a spa. This is an unusual luxury: so often we find merely a few scraps of information about any well, perhaps only its name remains. But people in Purton are proud of their healing well which became a spa, and this century local historians have researched its history in some detail. But in doing so they have recorded accounts of the well and its establishment as a spa as told by local people this century, and a careful examination of these accounts reveal that today’s view of the events is interestingly skewed away from the facts as recorded at the time. In some respects it is quite difficult to discover the facts in the development of Purton Spa because folklore has enhanced them somewhat over the years. Let’s examine a contemporary account of the spa’s development written by a Purton local historian (Robbins 1991, pp.976-8), taking his information partly from written and partly from oral sources. * For several centuries, the poor people of Purton Stoke had used as a medicine, a mineral water which bubbled up from a hole in one of the fields. As far as we can tell, the well does seem to have been used for at least 150 years prior to the 1850s. One source records that 'One inhabitant, by name Isaac Beasley, when in the 94th year of his age, and being still in possession of extraordinary powers of memory and great physical strength for his years, avowed that all his life he had been in the habit, when out of health, of drinking this water, and it was certain to put him right. He remembered his father took this water as a physic, and that large numbers of folks in his youthful days took the water from Salt’s Hole for all manner of diseases, and it mostly cured them' (Anon. 1881, p.6). I have so far found no documentary evidence suggesting use prior to about 1700, although this does not, of course, mean that it did not take place. * It was said that the local gentry and doctors placed no value on it. This seems to be folklore, as no contemporary accounts state this, but the actions of Dr S.C. Sadler support this, as we shall see. * The spring flooded the lane in the winter months, so the owner, Mr S.C. Sadler upset the villagers by draining the area and having cartloads of soil thrown around the spot. He had railings placed about the hole but the villagers broke the lock to obtain the health-giving water. In Bell’s Messenger (1860), the earliest printed source as yet available to me, we read, 'At Purton… is a field which time out of mind has been called Salt’s Hole… some years back it became the property of the present owner, S.C. Sadler Esq., JP etc. for Wilts, who at that time caused it to be drained, in doing which a well of water from which the field took its name, was filled in and destroyed. This circumstance, it appears, at the time gave rise to much murmuring and dissatisfaction on the part of many of the poor people in the parish, who stated that when they were ill they could always be cured by drinking the water; and one old man in particular… had given such fabulous accounts of the diseases cured in olden time by the water from Salt’s Hole, that the owner was induced to search for the locale of the well, which was, after some trouble, found indicated by a slight sinking of the earth, the surface of which had a white efflorescent appearance. A small excavation being made, the water quickly came bubbling up…' and it goes on to say that the news spread like wildfire and people came to drink the water (Anon. 1881, pp.7-8). This is markedly different from the 1990s account whose tone is that of obstructive landlord harassing the local poor. The contemporary account is rational and balanced, showing a new landlord who drained a field, became aware of local dissatisfaction, listened to local opinion and was sufficiently impressed to open the well up again. * Mr Sadler is said to have contracted a serious illness and decided to try the water himself, obtaining an immediate benefit. I have so far found no account of this in the documents published at the time. It seems to me that if this had been true, Sadler would surely have used this ultimate recommendation in his advertising literature and publicity. This seem to me to be pure fabrication, invented to fit the requirements of the narrative. The curator of Purton museum, local author and historian Alec Robbins, confirms that locally the story is that Dr Sadler fell ill and was cured by the healing waters. * Two eminent chemists analysed the water and found its composition to be unique. Dr Voelcker carried out the full analysis. Dr Dundas Thompson also tested the water, found valuable salts in it, and recommended a full analysis (Anon. 1881, pp.5-6). When the different elements in the accounts are placed side by side it is clear how subtly different they are (see table). What we have here is a gentle skewing of the facts so far as we can establish them from contemporary accounts (and these may be themselves prejudiced in favour of Dr Sadler, a respected landowner and pillar of the community). The villagers are portrayed (by their present-day descendants) as having the wisdom of the years, knowing better than the established professionals and gentry. Outraged because access to their traditional healing waters is denied them, the heroic villagers assert their rights and break the locks which exclude them. Then, by a stroke of fate the narrow-minded doctor himself falls ill and is induced to try to water – which cures him! Only then do ‘eminent chemists’, the wise men of science, test the water – which turns out to be unique. Local custom and wisdom is vindicated, and right triumphs over repressive landlords. Purton Spa: a brief history The spa’s heyday was between 1859 and 1870. It was never a true spa – there was no social life surrounding it, no assembly rooms, hotels, attractions and social whirl. All there was an octagonal pump-room over the well, a manager’s house (Spa House beside the well) and for a brief time a boarding house in Purton, which was there so briefly that nobody now seems to know where it stood. Contemporary writers about Purton work hard to find positive things to say about the Spa. They describe the water as 'Clear and bright, resembling ordinary spring water. There is scarcely any odour or taste whatever.' And that would have been very welcome to those used to the assertively-flavoured Bath waters, for example. They mention the fine air, the quietness of the village which is so attractive to 'those whose minds need the solace which only perfect rest from the harassing cares of busy every-day life can give'. Much is made of the fact that Purton 'boasts a station of its own'; and that Dr Sadler is at hand to supervise the daily regimen of the invalids seeking a cure. But the picture which emerges very strongly is that of a commercialised medicinal spring in a very rural community with little or no social life to attract those who like a little diversion with their medicine (Anon. 1881, p.4; P. de V. 1879, p.7). The Spa waters were bottled and sent to all parts of the country and to the continent between 1869 and 1880; and this trade was resumed in the next phase of the spa’s life. When he retired from the army in 1921, Sergeant Fred Neville bought Spa House, and began selling the water along with his own produce, in the villages round about, first by pony and trap and later by car. From 1927 to 1952 bottled Purton Spa water was commercially available once again. Unlike the Victorian bottles, which were stoneware – one survives in Devizes museum – Neville’s bottles were clear glass with an authoritative label showing the Voelcker analysis and the recommended 'Ordinary dose: Half-pint at bed-time, and the same, or more, an hour before breakfast the following morning, subject to variation according to nature of disease and effects produced.' Like Dr Sadler, Fred Neville got the water professionally analysed. Purton museum has the letters sent him by the Pathologist of the Royal Mineral Water Hospital in Bath, whose name is almost illegible but appears to be John W. Munro. His 1929 analysis checked for radioactivity and iodine content. When fresh, the water is 'sensibly radio-active', that is, it contains radon gas at a concentration of 0.165 millimicrocurie per litre. It contains 262.57 gamma units of iodine, which Munro stresses is 'an important factor from a medical point of view'. Nowadays we know all too much about it, and we look askance at radioactivity, but at this period it was a fashionable healing attribute. Neville stopped delivering locally during the 1940s when petrol rationing, a 20% tax on table water, and the ready availability of liver salts conspired to make the Spa water a relatively expensive commodity. The last entry in the ledger records a consignment of water sent out by rail in June 1952 (Compiled from Robbins (1991), pp.97-8, and documents and objects in Purton museum). Salt’s Hole today Purton Spa as it is today (1995) So what has happened to Purton Spa? Does anyone drink the waters any more? The well-house is still standing, though a little dilapidated. Inside the marks of damp are evident, not surprising since there is close on ten feet of water in the well, and it is sealed only by a stone cap with a wooden lid to cover the hole where the pump used to sit. In 1997, Alec Robbins told me that Fred Neville’s daughter, Mrs Joy Morris, still lives in Purton and that she still gets water from Salt’s Hole. I wondered whether there was any more use of the well locally, in the traditional way – local people going to get the water in spite of it being on private land. In September 1997 I spoke briefly to the owner, Mr Roberts, who told me that 'various people about the place' still drink the water. There used to be a door on the well-house, but he has had to take it off and store it in his barn, because people kept breaking in. I got the impression that this was how he knew people were still drinking the water – in the good old traditional way they were getting to the healing waters in spite of the repressive landlord who was trying to lock them out. I should add in his defence that Mr Roberts was described to me as 'a charming American gentleman', and that he has quite unrepressively invited me to call in and see the documents he has relating to the spa. So Salt’s Hole seems to have come full circle, from healing well to commercial spa to – it seems – healing well again. As a folklorist, ever on the look-out for living folklore, I find this continued use extremely satisfying." To see the Salts Hole in context see this image http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/1635389